Bank & FinTech Collaboration Models – How Big Banks Plan Fight the Big Tech Challenge

by Company Announcement August 16, 2018Sometime around the tail-end of 2010 the banks started realising that something called a FinTech could be a threat to their business. This is a time when some senior executives in the bigger banks were asking the digital leaders if it would be possible to slow down internet adoption by their customers (true story).

Author: Alessandro Hatami*

The banks’ natural reaction was initially of disbelief and denial. As the likes of Transferwise, Zopa, SoFi and Fidor started gaining momentum, this was followed by fear with boards buzzing with stories about a Blockbuster moment. Bank ‘Innovation teams’ were hurriedly set up to fight the FinTech wave. Then, investment by the banks in internal digital development started growing – fast. The banks were going to beat the FinTechs at their own game.

But things did not go as expected. The big spend in innovation by the banks did not stop the FinTechs from being disruptive and from growing their customer bases. The banks realised that they didn’t have what it took to succeed. At the same time the FinTechs realised that even though they had better skills, were more agile and were becoming increasingly better funded, breaking the domination of the incumbent banks was going to be hard.

So Banks and FinTechs started realising that the future of both lies in collaboration. We are now seeing that on both sides of the divide – many are keen to work together.

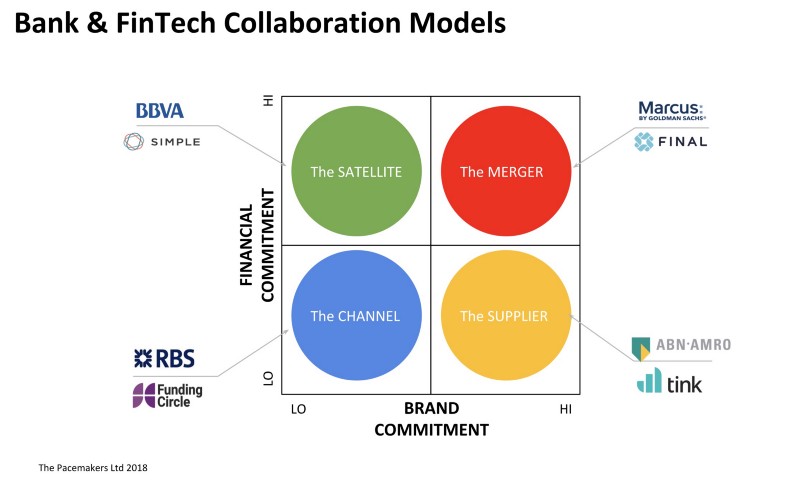

These collaborations can take many forms and it is worthwhile to group and describe the most common models. These can be summarised into four main groups:

The Channel

This is when the bank helps the FinTech to sells its products to the bank’s customers. The benefit to the bank is to offer a new product or service to its customers, spending relatively little time, effort and capital in creating it. The bank also gets good insight on whether customers like the proposition so that it can decide what to do next: walk away, build in-house or deepen the relationship with the FinTech.

The FinTech benefits from access to new customers and new sales, improvement to their brand through association with the (ideally) well-respected bank and market insight to refine their products. Customers get a new offering from their bank that they may find interesting. They also get reassurance from the bank that FinTechs can be trusted with their money.

The risks to the FinTech and customers are close to nil as It usually provides little exclusivity and is not directly affected by bank operational complexity. Ideally the bank could learn from the way the FinTech operates, but if not managed carefully, it risks potentially nurturing a competitor in exchange for market intelligence. Also worth asking is who is responsible if the customer is hurt by the FinTech? Even if legally the bank can insulate itself from things going wrong at the FinTech the PR and even regulatory pressures may force it to take on the liabilities.

Examples of this model of collaboration is the collaboration between The Royal Bank of Scotland and Funding Circle to deliver SME loans and the partnership between JPMorgan and OnDeck.

The Supplier

In this scenario the bank engages with the fintech as if it were a supplier. A new proposition is created by integrating the capabilities of the FinTech within the bank’s offering. To the customer the offering looks like the bank is providing the service, even if there may be some statement on the contribution of the FinTech in the offering’s terms and condition fine print.

To the bank this is a good way to explore new propositions with customers. If successful it will improve the relationship with customers and provide insight on the most desirable next steps with the FinTech with little brand erosion as a result of collaborating with a third party. It also does provide a certain flexibility as the bank can pull the plug with relatively low cost. We can also see the bank making a minority investment in the FinTech

One caveat is that this model often does not provide exclusivity, as the FinTech could collaborate with other banks.

A few examples of this is the partnership model is the collaboration between Bud and First Direct (part of HSBC) where they are engine behind the First Direct Artha app and the partnerships Swedish firm Tink has created with SEB, ABN Amro and Paribas Fortis.

The Satellite

This is a progression of the Supplier model. The bank decides to acquire a FinTech but then leaves it relatively independent. The FinTech receives an injection in capital, implicit validation of their business model through the investment of the bank and possibly access to the bank’s customers. The bank can see this investment as the means to experiment in a specific business area without impacting their existing operations. With this approach the bank gets good market intelligence and also ensures exclusivity and control of a new proposition.

By leaving the FinTech separate the bank also shields it from the any detrimental impact from the mismatch between the way a bank is run and the needs of an earlier-stage business. Also, this approach may make it easier to retain talent. Many talented employees of FinTechs may not want to be part of a big, structured legacy organisation like a bank but will work in a FinTech owned by a bank. This setup will help their retention.

There are two main risks. How do you retain the founders after they have cashed in? Earnouts are a good tool but the “fire in the belly” urgency of a pre-sale FinTech will be lost. Also, should the experiment fail for any reason (low customer appetite, something systemic within the FinTech, change in regulation etc.) the bank may have to write off a substantial investment.

A good example of this is the acquisition of Simple Bank by BBVA. Simple has been left relatively untouched operationally and a customer would have to look hard to realise they are in fact a BBVA company. More recently the acquisition of Nickel by BNP Paribas is another example of one owner two brands.

The Merger

This is a more traditional acquisition model. A transaction takes place with a clear understanding that the FinTech will be integrated and rebranded within the bank. This gives the bank the benefit of delivering innovation under its own brand increasing customer goodwill and stickiness.

On top of the risks with the Satellite model, we add the risks associated with the integration of two businesses that probably have very different cultures and operating models. Unless managed very carefully the bank will find itself having invested in as asset that is deteriorating in value.

An example of this has been the acquisition of Final by Goldman Sach’s consumer bank Marcus. The Final brand is gone and the team and customer portfolio have moved over to Marcus. In fact Marcus is a firm believer of growth through acquisition, having bought over 37 FinTechs between 2013 and 2017.

It is becoming clear that in the coming months and years we will see an increasing number of banks collaborating with FinTechs. Choosing the best way forward is going to be a determining factor in ensuring the success or even the survival of both the incumbents and the challengers. Especially as a third contender is about to enter the fray: Big Tech.

GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon) are all taking steps in financial services. Apple has launched ApplePay – a great product but with niche appeal for now. Google still supports Google and Android Pay but its efforts are not worrying the banks. Facebook is experimenting with P2P payments with limited success, but the potential is still there. Last but not least Amazon – their upcoming US current account (supported by JPMorgan) is sign of things to come. If they follow the example set by Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent in China the real battle for the future of financial services has not yet started.

*This article first appeared Alessandro Hatami’s Medium.

“Innovation is meaningless without implementation.” Opinionated serial corporate innovator. Founder of The Pacemakers. https://www.linkedin.com/in/aehatami

“Innovation is meaningless without implementation.” Opinionated serial corporate innovator. Founder of The Pacemakers. https://www.linkedin.com/in/aehatami